Calculating the experience of riding a bike

A confession

Don’t tell anyone, but I’m a bit of a math geek. The math I use day to day is pretty simple, rarely more interesting than divvying the bill and adding tips at restaurants, but it’s more complex math that makes me swoon.

Don’t tell anyone, but I’m a bit of a math geek. The math I use day to day is pretty simple, rarely more interesting than divvying the bill and adding tips at restaurants, but it’s more complex math that makes me swoon.

I’m smitten with mathematical equations that eloquently express universal truths about the natural world. About man-made designs. And most of all, about human nature. They’re kind of magical.

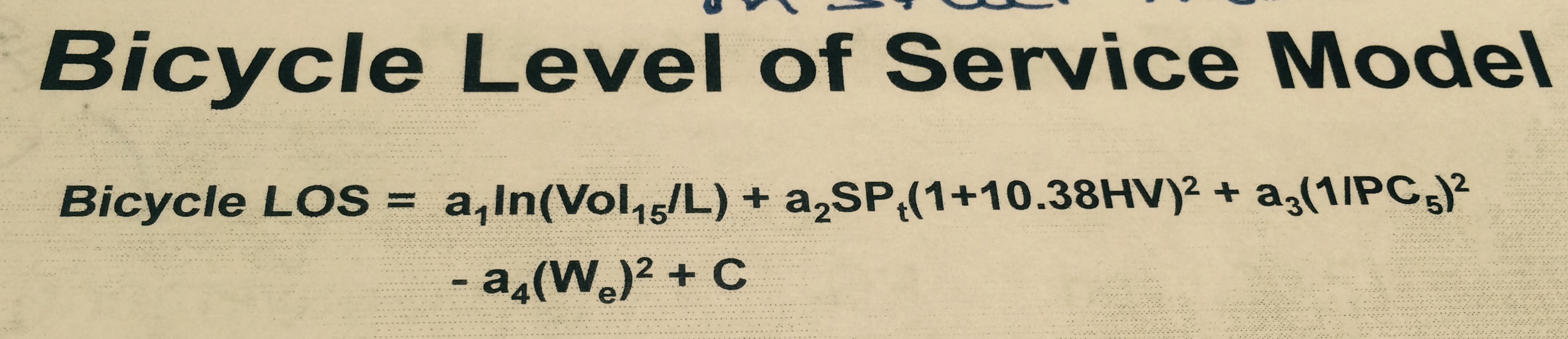

Knowing this, imagine the quickening of my pulse and the slight dilation of my pupils last Monday when I cracked opened my 205 page “Bicycle Facility Design” workbook and spotted:

My friends, THIS translates the human experience of riding a bike on a street into engineerese. It’s a formula that asks the same questions you do when thinking about which street to ride on.

- What’s the condition of the pavement? PC5

- How many vehicles are there? Vol15

- How many of those are really big? HV

- How fast are they traveling? SPt

- How much road space do cars and bikes have to share? We

Finally, like most great math formulas, there’s a natural logarithm and a constant thrown in and (voilà!) you have a numerical expression for riding a bike.

What does it mean?

An answer close to 1.5 indicates most people feel pretty safe riding a bike along that stretch of road. If the answer tips 4.5, it’s probably not where you would ride unless you absolutely had to. And 5.5? Don’t go there.

An answer close to 1.5 indicates most people feel pretty safe riding a bike along that stretch of road. If the answer tips 4.5, it’s probably not where you would ride unless you absolutely had to. And 5.5? Don’t go there.

This was one of many formulas introduced at the Bicycle Facility Design Workshop in Carbondale, hosted by the Colorado Department of Transportation. With 23 transportation planners and engineers from across Colorado, I spent nine hours delving into the technicalities of how to design roads safely.

As someone with no previous transportation engineering experience, I was amazed—if not surprised—by the complexity of designing bike facilities.

What problem are we solving?

What problem are we solving?

Shortly after lunch, while calculating stopping sight distance [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][S=(V2/(30(f+G)))+3.67V], I realized the equations, engineering standards and detailed schematics in our book all answer the question: “How?”

There are no proven formulas for “why,” “when,” “where” or “who.” Yet, these are the questions that we need to answer to get to the “how.”

Questions like: Why do we need safe spaces for people to ride bikes? When must a city, county or state build roads safe for folks who ride for transportation or recreation? Where aren’t people riding because they feel unsafe? Who will benefit from more opportunities to ride a bike?

This is where math fails us, but we don’t need a formula to know that our streets must be improved to be safer for all. If we don’t set the expectation that streets should be safe for everyone, all we get are well-designed bike facilities in places people already ride.

This is where math fails us, but we don’t need a formula to know that our streets must be improved to be safer for all. If we don’t set the expectation that streets should be safe for everyone, all we get are well-designed bike facilities in places people already ride.

Across the country, we are in a process of changing the problem we’re solving from: “How do we move more cars quickly?” to “How do we move more people safely?”

Bicycle Colorado and the Colorado Pedals Project are partnering with organizations such as CDOT to make Colorado the most bicycle-friendly state in the nation. We’re grateful the math is in place to support good design, but we also need communities to elevate the value of cycling by asking the right questions (why, when, where and who) and saying “yes!” to cycling infrastructure.

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Leave A COMMENT

Our twitter feed is unavailable right now.

COMMENTS (4)

Kenneth Jessett -

People ride when it is safe to do so or because they have no other transport option. Too many times riders venture out on roads that are not fit for the purpose. Drivers will never understand the reasonableness of bicycle riding on public thoroughfares and the antipathy this creates means there will always be conflict, and usually it is the cyclist who suffers, not the driver. Until and if ever drivers recognize that cyclists are not the enemy, there will continue to be an uneasy relationship between the two. Cycling works in such countries as Holland because there is an overwhelming number of bikes on the public roads and drivers have come to terms with them. The question then becomes one of: How do we educate motorists to accept cyclists and how do we damper drivers’ impatience and anger when they do met us on the road?

Rachel Hultin -

Thanks Kenneth. I’m interested in hearing your response to your question “How do we educate motorist to accept cyclists and how do we damper drivers’ impatience and anger when they do meet us on the road?“

Bob Cooper -

I`m an avid cyclist. There are some roads that just aren`t able to handle cars and bikes. Stay off them. Figure another route. Don`t give drivers a reason to be pissed at cyclists.

Rachel Hultin -

Good point that some roads just aren’t designed to safely accommodate bikes and cars. The more we can remember that almost everyone who is behind the wheel of a car also has a bike and vice versa. The more we can advocate for separated facilities for bikes and cars, the more we can reduce the conflict and the more we can feel like “we”, not “us v. them”. Thanks for being a part of the conversation and for ideas on how to avoid conflict to help find common ground! Onward…