Bicycle Colorado, the state’s leading organization championing the safety and interests of bicyclists, and Obvio.AI, a technology company dedicated to curbing reckless driving, have partnered to complete a landmark driver behavior safety study in Colorado. After conducting 30-minute observations at 196 intersections across 25 Colorado cities and counties, we identified nearly

7,900 violations among just over 49,000 vehicles

The study, the most comprehensive of its kind in Colorado, shines a light on the driver behaviors that contribute to traffic violence, which is a growing public health epidemic. In addition to accelerating infrastructure changes to prioritize safety over vehicle speed, the study calls for a comprehensive automated enforcement strategy as a scalable, unbiased way to save hundreds of lives each year—especially those of vulnerable road users.

From 2021-2025, 3,562 people were killed in traffic crashes in Colorado, and over 16,000 suffered serious, often permanent injuries. Put another way, on any given day, approximately two people will die, and ten will suffer a serious injury while engaging in the routine activity of traveling around their community. Or consider this: for two decades, traffic violence was the leading cause of death for children and teenagers in the United States. Today, it is second only to gun violence.

The explanation begins with a simple truth: people are fallible and can make poor and sometimes truly awful decisions while driving. Instead of applying this understanding when designing our transportation system, we did the opposite and built a system that amplifies the negative consequences of our poor choices.

Many of our roads are designed to prioritize vehicle speed and throughput at the expense of safety—particularly for people outside of vehicles, such as bicyclists and pedestrians. Far too many streets encourage speeding, including those that cut through mixed-use neighborhoods where people are walking, biking, and rolling.

Over time, Americans have increasingly chosen larger and heavier vehicles with wide, high front-end profiles. Over the past 30 years, the average U.S. passenger vehicle has gotten larger, about 4 inches wider, 10 inches longer, 8 inches taller, and 1,000 pounds heavier. The average hood height of passenger trucks increased by at least 11% between 2000 and 2021, and their average weight increased by 24% between 2000 and 2018, according to a Consumer Reports analysis of industry data.

Distracted driving has become normalized, driven in part—but not solely—by smartphones and increasingly complex dashboard screens. An “everyone does it” mentality has taken hold, creating a dangerous social norm that treats distraction as acceptable behavior, unlike driving under the influence, which is widely condemned.

Traffic laws are not enforced consistently, often due to limited funding and staffing resources. This lack of enforcement effectively signals that dangerous driving behaviors are tolerated, undermining safety for everyone on the road.

Fortunately, just as the current transportation system was the result of our choices, we can choose another path. We can choose to reconfigure our roads and adopt & enforce evidence-backed policies to improve safety and save lives. These are the choices we strongly urge decision-makers to make.

In response to advocates pushing for solutions to improve road safety, skeptics often argue that the vast majority of people are excellent drivers (despite fatality data) and that the recommended safety measures, though often supported by research, are attempting to solve a problem that does not exist.

This led us to ask:

This summer, our team partnered with Obvio AI, a traffic-safety artificial intelligence company, to run what we believe is the most comprehensive driver behavior study in Colorado. For the first time, we have better insight into the underlying driver behavior that contributes to traffic crashes, fatalities, and injuries. We hope this data prompts urgent action from community members and government officials and helps inform solutions that make streets safer for everyone.

We observed more than 49,000 drivers across 196 locations in 25 communities. We selected a diverse set of sites—urban, suburban, and rural—with sufficient traffic volume and where the community had flagged safety concerns. We intentionally spread beyond the high injury network to see what was happening on roads with high, medium, and low volumes. The table below reflects the cities and counties we visited. The map identifies the specific locations.

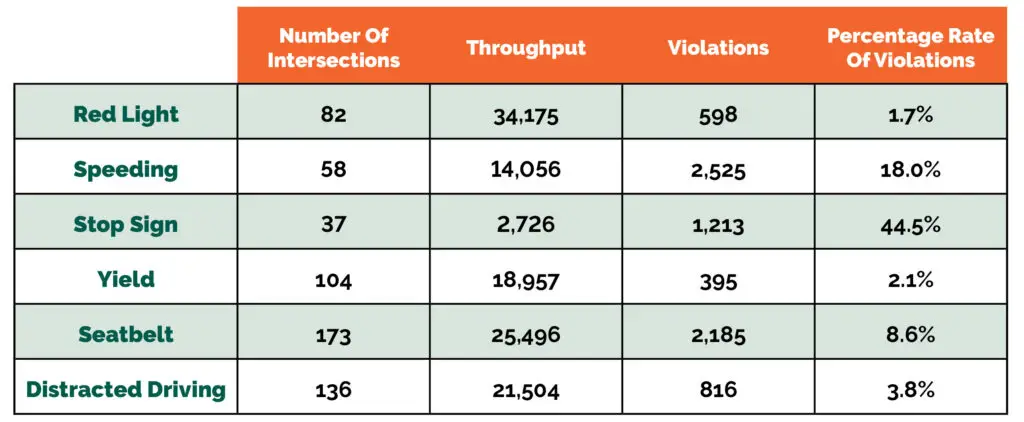

Using dual setup cameras and AI, we analyzed whether drivers complied with the following laws: posted speed limits, traffic signals, stop signs, yield signs, mobile phone use, and seatbelt use. We monitored a mix of different intersection types: 82 stop lights, 37 stop signs, and 104 yield signs. Finally, we noted instances of violations in relation to people biking, walking, and rolling.

For speeding, the study documented any instance in which a driver exceeded the posted speed limit. The purpose of this data collection was not to identify individual drivers for enforcement, but to develop a broader understanding of prevailing driving culture and compliance patterns.

The following table summarizes key findings.

Note: Throughput for distracted driving and seatbelt use reflects the number of drivers who were clearly visible.

Below are locations with the highest frequency of dangerous driving, with high volume and/or large pedestrian traffic:

In aggregate, the data suggest that most people in Colorado obey traffic laws, which is expected. However, during the 30-minute windows of monitoring over 196 intersections, a staggering 7,867 drivers committed a moving or driver violation out of the 49,242 vehicles captured by our cameras. When extrapolated, the data projects a staggering 200,000 daily violations from just these observed intersections.

Most people driving safely is not good enough. There are few, if any, human-designed systems where the failure rates reflected in this study (traffic violation % = failure rate) are acceptable. The same is true for our transportation system. And the downstream impact of this poor driving—hundreds of lives lost and thousands injured in traffic crashes yearly—supports this conclusion.

It’s easy to point the finger at drivers—if only they would slow down and pay attention! Yes, drivers should do this, and we should continue to educate people on the rules of the road and safe driving habits. But it’s more complicated.

At its core, traffic violence is a public policy failure. For decades, government officials prioritized vehicle speed and driver convenience over human life. We built and continue to maintain this system, despite the immense human and economic costs and despite having the knowledge and resources to prevent crashes and tragedies. Yes, it is within our grasp to eliminate traffic violence entirely.

Experts in traffic safety commonly describe the solution as the three E’s: engineering, education, and enforcement.

Design roads that naturally slow vehicle speeds and provide dedicated, protected spaces for people biking, walking, and rolling. Infrastructure changes driver behavior and can mitigate the impact of poor choices.

Enhance public awareness of traffic regulations and safe driving behaviors. The more people who have this knowledge and develop safe driving habits, the better.

Adopt and enforce laws that promote safe driving. Enforcement creates accountability, and accountability changes behavior.

Engineering—or changing the infrastructure—is a game-changer; however, experience tell us that it requires significant time (frankly, much more time than it should) and capital investment, making it challenging to scale. Nevertheless, we must double down efforts to change the built environment, and we must do a much better job of enforcing traffic laws.

The evidence is clear that the consistent enforcement of traffic laws, with timely and meaningful consequences, changes driver behavior and saves lives. Yet, Colorado has moved in the opposite direction. Since the late 2010s, officer-initiated traffic enforcement has sharply declined statewide. According to an analysis by the Common Sense Institute, violations filed under Colorado’s primary traffic penalty statute dropped 54% between 2018 and 2024. This isn’t a perfect measure, and enforcement varies across communities, but it sends an overarching, clear signal: today’s drivers face fewer consequences for dangerous behavior.

Unlike traditional enforcement—which depends on an officer being in the right place at the right time—automated systems provide consistent, unbiased accountability at a lower cost to taxpayers. The positive impacts of automated enforcement are clear. Here are a few examples:

On Highway 119 in Boulder, where the speed limit is 50 mph, automated speed cameras were installed in July 2025, resulting in a reduction in the number of people speeding by

80%

In Oregon, speeding dropped by

23.7%

In Maryland, the number of vehicles traveling more than 10 mph over the speed limit fell by

62%

In Washington, D.C., the number of vehicles traveling more than 10 mph over the limit fell by

82%

Our partners at Obvio have also seen how automated enforcement can drive behavior change quickly: in a deployment in Prince George’s County, Maryland, they were able to reduce stop sign running in school zones nearly 70% in just 4 months.

Since 2023, Colorado’s Governor has signed three bills into law that empower state and local governments to expand the use of automated traffic enforcement to address a range of dangerous driving behaviors, such as:

Municipalities are also allowed to enforce compliance with dedicated bus and bike lanes.

With a clear state legal framework in place, it’s time for Coloradans to demand immediate action and for government officials to thoughtfully, yet urgently, implement this solution, which has been proven to save lives.

Access the complete raw dataset from the driver behavior study, including all recorded violations and observation details. Use the data to support research, policy decisions, and safer streets.

Please contact us to learn more about this study and how to use automated traffic enforcement to make your community’s streets safer for everyone.

Peter Piccolo

Bicycle Colorado Executive Director

[email protected]